Due to a series of geopolitical events, the main global economic blocks are now affected by the process of geoeconomic fragmentation that reshapes global trade and investment flows.

Two shapes of international fragmentation

International economic fragmentation was once seen as a natural by-product of intensifying global trade flows and international re-organization of production. The process implied that “segments (production blocks) are located in different geographical areas, perhaps in different countries, and that they may be undertaken by different firms.”1 The fathers of the concept also noted that “[a]n important advantage of fragmentation is that it allows production blocks to be moved around so that components are produced in the best possible location.”2

The current meaning of fragmentation has changed radically. Today experts in the field speak about geoeconomic fragmentation to refer to “a policy-driven reversal of global economic integration often guided by strategic considerations”.3

This paper documents the recent developments in geoeconomic fragmentation in the three major economic blocks – the EU, the US, and China – across the two main economic dimensions – trade and foreign direct investment flows.

A global view at the cracks to trade and investment

The first discernible fractures in the global economy began to surface in the aftermath of the 2007/2008 great financial crisis. Both cross-border trade and investment flows were strongly affected by the underlying financial and economic turmoil (Fig. 1).

But these trend reversals have been significantly reinforced by a series of more recent events, predominantly rooted in geopolitics. A pivotal role in sparking economic cracks to the global economic order played the Brexit vote, the US-China trade dispute, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The involvement in policy interventionism of the three main economic blocks, the EU, China and the US, has been strong and intensifying. However, whereas the EU is more intensively affected by harmful interventions of others than it imposes against others, the opposite is true for China and the US. For both countries, the number of harmful measures implemented exceeds the number of measures affecting them by a large margin. In the United States, there has been a notable surge in protectionist interventions, particularly evident since Donald Trump assumed the presidency in 2017, but the trend continued under the Biden Administration (Fig. 3).

Policy-driven measures are on the rise

Heightened geopolitical tensions have recently contributed to an increase in protectionist relative to liberalizing measures in international trade (Fig. 2). The bulk of these interventions directly relates to trade of goods and services, e.g. via export or import ban, tariffs and quotas, or cross-border investment through foreign investment policy measures. However, indirect interventions can also affect trade and investment flows through, e.g. capital controls and exchange rate policy or localization policy. There is also an increasing reliance on cross-border restrictions justified on grounds of public health and national security.

The involvement in policy interventionism of the three main economic blocks, the EU, China and the US, has been strong and intensifying. However, whereas the EU is more intensively affected by harmful interventions of others than it imposes against others, the opposite is true for China and the US. For both countries, the number of harmful measures implemented exceeds the number of measures affecting them by a large margin. In the United States, there has been a notable surge in protectionist interventions, particularly evident since Donald Trump assumed the presidency in 2017, but the trend continued under the Biden Administration (Fig. 3).

Cracks are evident, but the big three are differently affected

The proximate result of the rise in protectionism in the three major economic blocks is visible in the changing intensity of their respective cross-border trade and investment relations. But the underlying impact differs much across the blocks and categories of flows.

For trade flows, Figure 4 shows the evolution of the trade openness, expressed in terms of the sum of exports and imports as a percentage share of GDP. The EU’s relatively high trade openness remained stable, despite the growing geopolitical tensions. At the same time, both the US and China have recently experienced a non-negligible retreat in their respective trade openness. Figure 5 shows that this process regarded both imports and exports.

In the US, this trend reversal corresponds with the more general ‘slowbalization’ process, observed on the global scale. For China, the reversal began earlier. The likely drivers of this are substantial economic policy adjustments, aimed at rebalancing the economy towards domestic consumption and away from export-driven growth, as well as at focusing on strategic industrial policy goals, including the reduction of dependence on supply of intermediate products from abroad. Indeed, the importance of both exports and imports relative to domestic value generation diminished over the years (Fig. 5).

Signs of (geo)economic fragmentation become much more evident when looking at the trade flows through a magnifying glass. An illustrative case regards Europe’s energy sector. While the EU's overall reliance on external energy sources has remained relatively stable, the origins of its energy imports have undergone significant shifts. In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU has significantly diminished its direct imports of Russian gas and shifted towards imports from the US and Norway. Whereas the EU natural gas import from Russia accounted for almost 24% in the second quarter of 2022, this share declines to 13% in the second quarter of 2023 (Fig. 6, left panel). A similar reversal away from Russia occurred for other energy sources (Fig. 6, right panel). Finally, with a remarkable exception of Austria and Hungary, all other EU members answered decisively to the Russia’s aggression with a substantial curb on exports to Russia (Fig. 7).

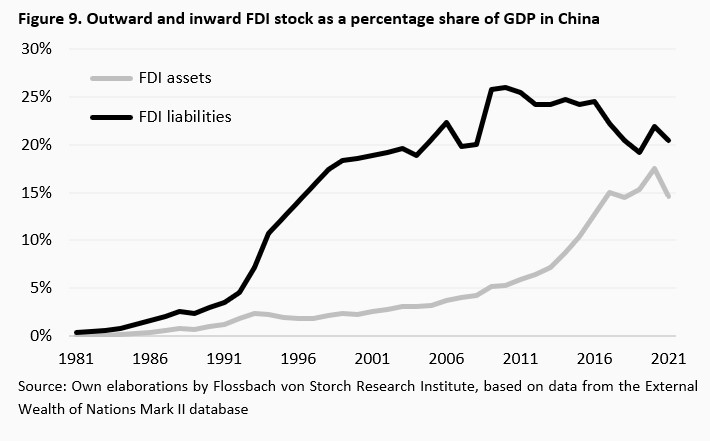

The setback in cross-border long-term financial investment activity in the three economic blocks is less pronounced than for trade relations, although the evidence for the EU is telling (Fig. 8). Since 2017, the degree of financial openness – measured as the sum of FDI assets and liabilities as a percentage share of GDP – has moved sidewards, likely driven by policy efforts aimed at limiting investment that could jeopardize security or public order. But also in China, there has been a slowdown in financial openness, the timing of which broadly corresponds with the EU’s experience. More precisely, the FDI stock of liabilities as a percentage of GDP reached its peak of 26% in 2009, moved sideward until 2016, and declined subsequently to 20% at the end of 2021 (Fig. 9).

Concluding remarks

Various geopolitical events have brought a shift towards geoeconomic fragmentation, involving intensified use of policy-driven measures and impacting major global economic blocs. As the evolving geopolitical landscape continues to shape trade and investment flows, it becomes increasingly evident that geoeconomic fragmentation is a new phenomenon of cross-border economic relations. Indeed, adapting to the underlying geopolitical changes is imperative for ensuring economic stability and security in an uncertain world.

Regarding the EU, it has already initiated some appropriate adaptation efforts, including, for instance, a more transparent and detailed framework to measure its (strategic) trade dependencies or an FDI screening framework based on a de-risking rather than a decoupling approach. These efforts are important as they strive to alleviate the impact of high-risk occurrences, thereby serving as a form of self-insurance against potential upfront economic burdens.

However, two sets of implications are still obvious. First, more concrete steps within the adaptation already undertaken and new initiatives are required. For the FDI screening mechanism, better coordination between member states is needed to prevent that the current patchwork of national rules and actions results in unnecessary uncertainty for – actual and potential – investors.4 Second – and foremost – the overemphasis of the EU’s very high standards especially with regard to environmental sustainability likely impedes the shaping of geoeconomic fragmentation such that it best serves the EU’s interests. Specifically, it dampens potentially attractive cross-border diversification opportunities. More importantly, however, it also puts excessive cost burden on domestic businesses, which are obliged to comply with a plethora of ever new and more stringent regulatory obligations. Such an approach is detrimental in two important ways. It not only threatens a timely achievement of environmental goals but also the EU's geopolitical cohesion. But since the latter is a fundamental prerequisite for the former, it would be advisable for the EU to reassess its priorities.

___________________________________________________________________________

1 Arndt, S. W., & Kierzkowski, H. (Eds.). (2001). Fragmentation: New production patterns in the world economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p. 3.

2 Ibid., p. 4.

3 Aiyar, S., Chen, J., Ebeke, C., Garcia-Saltos, R., Gudmundsson, T., Ilyina, A., Kangur, A., Rodriguez, S., Ruta, M., Schulze, T., Trevino, J., Kunaratskul, T., & Soderberg, G. (2023). Geoeconomic fragmentation and the future of multilateralism. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/2023/01.

4 The European Commission seems to be aware of these drawbacks and has already formulated plans in this regard in the proposal for a new regulation on the screening of foreign investments, available at: ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_363.

LEGAL NOTICE

One of the purposes of this publication is to serve as advertising material.

The information contained and opinions expressed in this publication reflect the views of Flossbach von Storch at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of Flossbach von Storch. Actual performance and results may, however, differ materially from such expectations. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. The value of any investment can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount you invested

This publication does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment, legal and/or tax advice or any other form of recommendation. In particular, this information is not a replacement for suitable investor and product-related advice and, if required, advice from legal and/or tax advisers.

This publication is subject to copyright, trademark and intellectual property rights. The reproduction, distribution, making available for retrieval, or making available online (transfer to other websites) of the publication in whole or in part, in modified or unmodified form is only permitted with the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

© 2025 Flossbach von Storch. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.