At least since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine the tight links with China must be regarded as a major source of political and economic risks. Contrary to expectations, closer trade relations with authoritarian regimes not only fail to induce shifts towards more democracy but can also be used by these regimes as a tool to blackmail its trading partners.

Specifically, currently almost 23% of the total imports of the EU come from China, followed by 11% from the US and around 8% from Russia. On the export side, the highest share of 18% is held by the US, followed by a 13% share of the UK, and 10% share of China (Figure 1).

Trade relations of individual EU countries with China

Among the three largest EU members, Germany has the strongest trade links with China, both in terms of imports and exports. The relationship increased significantly over the last two decades, rising from 3.4% to 11.9% for imports and from 1.6% to 7.6% for exports. Both France and Italy increased their trade relations as well compared with the beginning of the new millennium. France’s export dependency on China increased from 1% in 2000 to almost 5% in 2021. At the same time, France has managed to reduce its import dependency from 9.2% in 2015 to 6.7% in 2021, whereas Italy’s respective trade shares moved sidewards over the last decade (Figure 3).

Product-level vulnerabilities

Across the broad product groups, the strongest EU’s foreign trade relations exist for machinery and transport equipment. In 2021, the import share in this product group over EU-wide imports increased from 29% in 2010 to 32% in 2021 (Figure 4). The corresponding export share declined from 42% in 2010 to 38% in 2021 (Figure 5).

For the EU’s imports in almost all product categories reported in Figure 4, China plays a dominant role, reflecting the country’s rise as manufacturing superpower since the 1970s.

Whereas not every trade relation – especially on the import side – is toxic per se, it becomes so if it leads to “strategic dependence”. This is the case if simultaneously three conditions are satisfied:

1) The country/region is a net importer of a good.

2) The country/region imports over 50% of its total imports of the good from a single partner.

3) The partner possesses at least 30% of the global market share for the good in question.1

Under strategic dependence, it is difficult for the country to readily re-direct its imports away from the exporter, which is a dominant player in the global market.

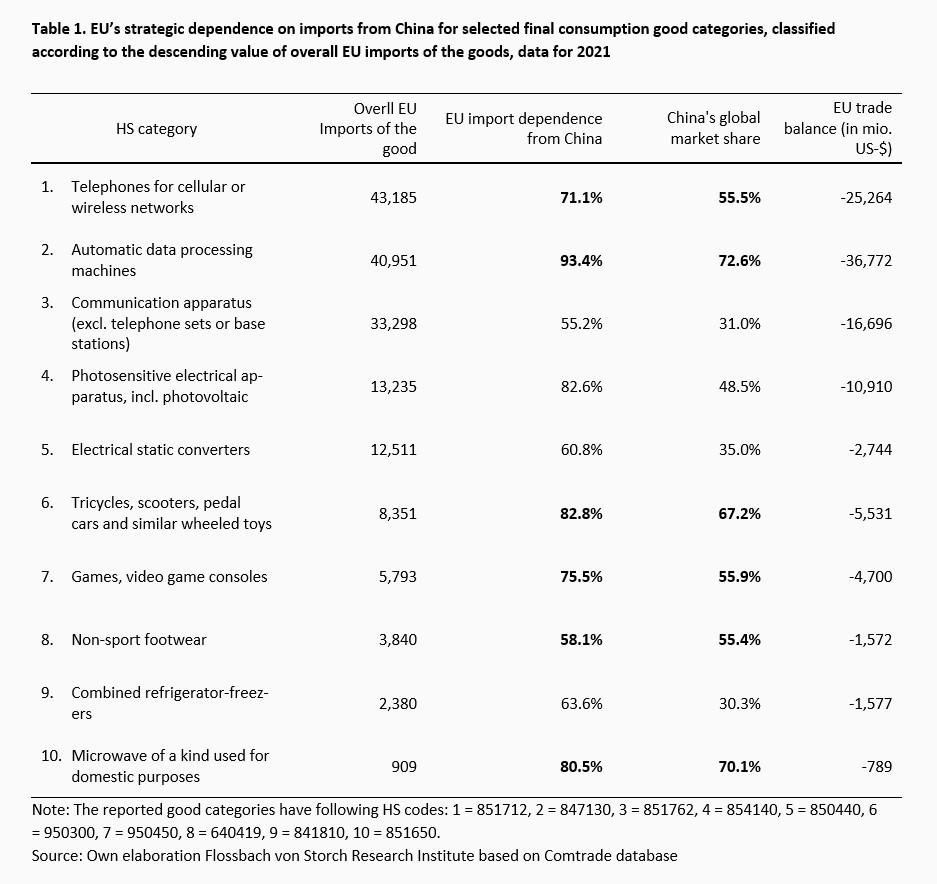

Following this definition, Tables 1 and 2 show strategic import dependences of the EU on China for main categories of final consumption and intermediate goods as of 2021. Both classifications are based on import values for 6-digit Harmonized System (HS) product categories.2 This allows a detailed view at the goods that are traded.

Among the top ten consumer goods, the strongest import dependence exists for important electronic devices. Specifically, in 2021, over 70% of EU overall imports of mobile phones originated from China, with China having almost 56% of global market share in this product category. Analogously for automatic data processing machines, wheeled toys, video games, and non-sport footwear the EU imports 93%, 83%, 76% and 58%, respectively, from China, with the latter possessing over 50% of the respective global market shares (Table 1).

But even more critical should be strategic dependences for intermediate goods. The unavailability of an essential production factor has the potential to disrupt the industrial production directly and indirectly along the supply and value chain. This is especially so if alternative suppliers cannot be easily and timely found.

The EU is particularly dependent in several categories of electrical machinery and equipment and parts thereof, in machinery and mechanical appliances, in base metals, glass, as well as in different categories of organic chemicals and inorganic chemicals (Table 2). Although they are not sophisticated technological goods, many of these products are critical inputs in the upstream production and make the entire industrial processes vulnerable to shocks. For instance, the EU's green energy industry – especially the wind energy sector – is highly dependent on China’s supply of magnetic metals that are essential component for wind turbines as well as modern electric motors. Also, minerals for power electric car batteries are typically mined and refined by Chinese companies.

Auswege aus dem Dilemma

Angesichts der sich verschärfenden geopolitischen Spannungen führt die wachsende wirtschaftliche Abhängigkeit der EU - insbesondere von China - zu einem Verlust an strategischer Souveränität. China hat bereits in der Vergangenheit gezeigt, dass es bereit ist, sein wirtschaftliches Erpressungspotenzial bei der Versorgung mit wichtigen Ressourcen zu nutzen. Bereits 2009 boykottierte China seine Exporte von Seltenen Erden, die für die Computerherstellung entscheidend sind. Unter der Führung von Xi Jinping wird das Land den Druck wahrscheinlich noch verstärken.

Die Verringerung der zugrundeliegenden Abhängigkeiten sollte daher eine Priorität für die Industriepolitik der EU sein. In erster Linie geht es darum, den handelspolitischen Rahmen und die wirtschaftlichen Anreize anzupassen, um zielgerichtete strukturelle Veränderungen zu fördern. Ein sinnvolles Instrument könnte die Abschaffung oder zumindest die deutliche Reduzierung von Investitionsgarantien für Geschäftsaktivitäten in und mit China sein.

Eine weitere wirksame Strategie könnte die Erschließung neuer Export- und Importmärkte durch zwischenstaatliche Abkommen sein, die bestehende Handelshemmnisse abbauen und attraktive Investitionsbedingungen schaffen. Die kurzfristigen Auswirkungen einer Abkehr von China könnten mit Effizienz- und Gewinneinbußen einhergehen. Mittel- bis langfristig dürfte sich die Diversifizierung jedoch auszahlen, wenn die neuen Kapazitäten ausreichend entwickelt sind, um Größen- und Verbundvorteile zu nutzen.

Die Diversifizierung wäre schon vor langer Zeit in den Vordergrund gerückt, wenn die EU ihre eigenen sehr hohen Standards in Bezug auf ökologische und soziale Nachhaltigkeit ernster genommen hätte. Stattdessen wird mit einer kurzsichtigen Strategie nicht nur die Nachhaltigkeit selbst, sondern letztlich auch die geopolitische Integrität der EU gefährdet. Da die letztere eine wesentliche Voraussetzung für die erste ist, wäre es höchste Zeit für die EU, ihre Prioritäten zu überdenken.

1 Die Definition und Messung der strategischen Abhängigkeit in dieser Studie folgt dem Ansatz von Zenglein, M.J. (2020), Mapping and recalibrating Europe's economic interdependence with China, Merics, China Monitor, November 18, 2020.

2 Das HS ist in 21 Abschnitte gegliedert, die in 99 Kapitel (zweistellig), 1.244 Rubriken (vierstellig) und 5224 Unterrubriken (sechsstellig) unterteilt sind.

Tabelle 1

LEGAL NOTICE

One of the purposes of this publication is to serve as advertising material.

The information contained and opinions expressed in this publication reflect the views of Flossbach von Storch at the time of publication and are subject to change without prior notice. Forward-looking statements reflect the judgement and future expectations of Flossbach von Storch. Actual performance and results may, however, differ materially from such expectations. All information has been compiled with care. However, no guarantee is given as to the accuracy and completeness of information and no liability is accepted. The value of any investment can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount you invested

This publication does not constitute an offer to sell, purchase or subscribe to securities or other assets. The information and estimates contained herein do not constitute investment, legal and/or tax advice or any other form of recommendation. In particular, this information is not a replacement for suitable investor and product-related advice and, if required, advice from legal and/or tax advisers.

This publication is subject to copyright, trademark and intellectual property rights. The reproduction, distribution, making available for retrieval, or making available online (transfer to other websites) of the publication in whole or in part, in modified or unmodified form is only permitted with the prior written consent of Flossbach von Storch.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

© 2025 Flossbach von Storch. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.